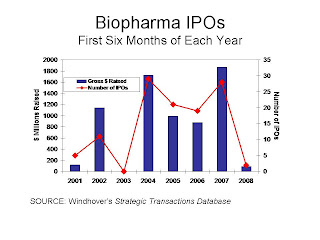

Historically speaking, the first half of 2008 has not been the worst period for biotech IPOs. But it’s damned close.

Historically speaking, the first half of 2008 has not been the worst period for biotech IPOs. But it’s damned close.

So far this year there have been at least two IPOs – BioHeart (which, after a year of trying, finally raised $5.8 million) and the Italian MolMed. In the corresponding period of 2003, no companies went public.

Not that IPOs “even several years ago” really constituted exits, argues Jean-Francois Formela, a partner at Atlas Venture. VCs have had trouble for the last decade or so getting out of their investments through public offerings – six-month lock-ups and small floats made selling significant positions difficult.

But the problem has only gotten worse. As public investors have grown more skeptical of biotechs, they’ve forced companies to move further down the road toward commercialization, which requires higher levels of investment. A VC-backed IPO in the mid 1990s might have raised $25 million privately; since 2006, the average has been $91 million.

Not too long ago – last year, in fact -- the IPO market was buoyed by so-called crossover investors, who, unlike managers of many public funds, have the ability to invest freely in private companies. They were looking to play the valuation gaps, both the gap between last private round and IPO and the gap between IPO and the price it reached when the stock started trading in earnest. Companies would bring in crossovers to top up the pre-IPO rounds and the crossovers would then take big chunks of the IPO.

But with the post-IPO disappointments of companies like Alexza (down 45% since IPO) and Orexigen (down 31%), or the delay of crossover favorites like Metabolex to get public, crossover investors are backing out of the private markets – and as they back out of private investments they’ve got less incentive to buy into new IPOs.

Indeed, over the last year or so, the U curve of biotech investing has grown more pronounced. Buyers can still ascribe high values to early-stage companies, like Alnylam or Sirtris but then the value per data point begins to diminish pretty rapidly until a drug gets approved – or even after. Anesiva, for example, lost almost 50% of its value between the approval of its first product, topical anesthetic Zingo, and the drug’s launch last month.

So crossover investors are looking for, finding or even constructing cheaper and safer opportunities in the public markets – as Deerfield has done with its clever senior debt facilities for Array Biopharma, Exelixis and Zymogenetics. The deals might not produce blockbuster returns, but in this bear market – according to Rodman & Renshaw, 82 public biotech companies are trading with less than one year of cash, nearly 50 with less than six months’ worth of capital; and 33 trading below cash reserves – they’re covering the downside pretty well.

There are certainly exceptions. Portola, for instance, just raised another $60 million, mostly from crossovers like DE Shaw and Brookside Capital, though at its previous round price. Even so, with a private valuation probably north of $250 million (it's raised a total of $218 million), it’s tough to see how public investors would be willing to swallow much of a step-up for a company with plenty of clinical and market risk remaining. Likely goal for investors: acquisition.

So VCs, and indeed some crossover investors, are now looking to new channels for exits, or at least pathways to exits. One idea getting increasing currency: PE-backed private-company acquirers. They’d have access to plenty of capital, just not public capital. And they’d be looking to build businesses all the way to profitability, at which point the mega-venture could be sold to someone else – as Reliant was sold to GSK or Kos to Abbott – or it could go public, as Atlas’ Formela says, “the old-fashioned way – as a mature business with a track record and good visibility on earnings.”

Such a company might pay to acquire a more typical later-stage private company at some discount to a standard IPO price; the acquired company’s VCs would stay in the game, accepting similar levels of dilution they now have to take in exit-less IPOs – but when the IPO comes around, it’s big and liquid enough to allow everyone who wants to get out to do so.

Certainly there’s enough money in private equity to accomplish the strategy. The problem is finding enough assets to justify it. There aren’t many products which have a relatively straightforward clinical and regulatory path through pivotal trials and, at the same time, the kind of sales potential to reward the investment.

For now, the talk of this alternative path to liquidity through private equity is just that – talk. The only real prop to biotech valuations, public and private, remains Big Pharma’s desperate hunger for products.

Friday, July 11, 2008

New Channels to Biotech Exits? Not Anytime Soon, at Least.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

If an organization wants help in M&A they should turn to free government organizations like the North of England that can assist them in identifying global strategic opportunities and can provide a host of resources at no cost. www.NorthEngland.com to see the value of conducting and collaborating in the UK.

Post a Comment